Syria’s “Bloody” Phosphates

Secret trade with EU enriches Assad regime and evades sanctions

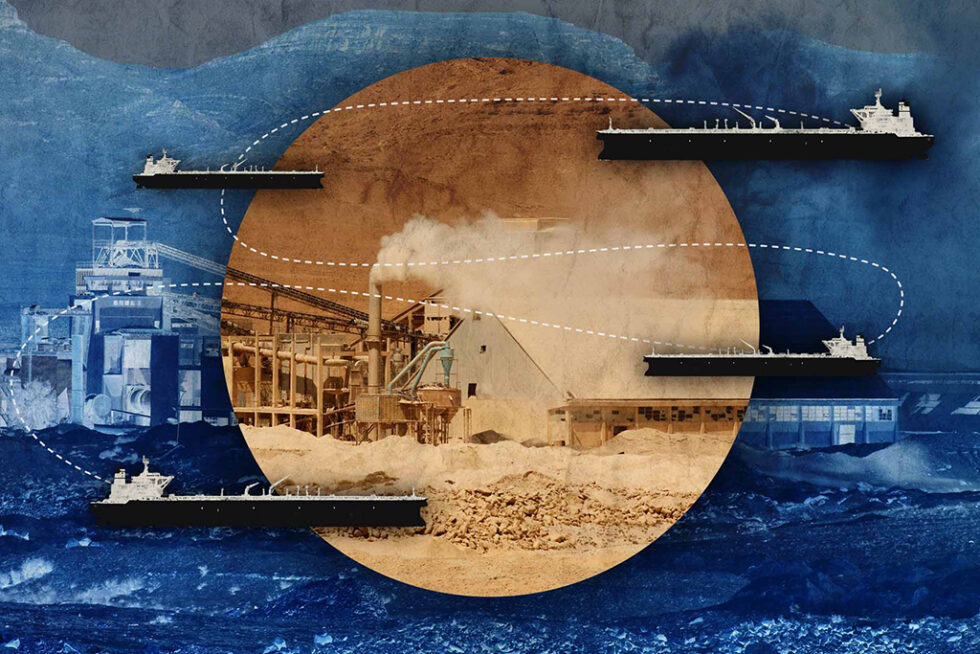

Millions of dollars’ worth of phosphates exported by a sanctioned Russian company in Syria have made their way into Europe’s fertiliser markets since 2018.

This murky supply chain passes through a complex network including a company controlled by a sanctioned Russian oligarch and crony of President Vladimir Putin, Syrian government entities and regime loyalists – all of them subject either to EU or US sanctions. The trade is abetted by shady shipping companies, middlemen and brokers.

Vessels carrying phosphates from Syria to Europe hide their activities by turning off their tracking systems on the way to Tartous port, Syria’s main phosphate shipping hub. They only turn them on again when their return journey is well underway.

The clandestine trade exploits a grey area in sanctions implementation, because neither the EU nor the US specifically prohibits the purchase of Syrian phosphates, allowing middlemen to take advantage behind a veil of shell companies.

Among EU countries, Italy started importing in 2020, Bulgaria in 2021, and Spain and Poland earlier this year, according to trade data. Serbia and Ukraine have also been major customers. Between them, these countries have imported more than $80mn in Syrian phosphates since 2019.

METHODS

Together with our investigation partner, the Syrian Investigative Reporting For Accountability Journalism (SIRAJ), we monitored shipping movements to- and from Tartous port, which handles the bulk of Syria’s phosphate exports via two specially customised loading berths.

Tartous port published data on its Facebook page specifying which vessels had docked, and their inbound and outbound cargoes. However, in 2020 the port suddenly stopped sharing updates and deleted its past posts.

We were able to reconstruct past shipments by recovering archived versions of the port’s website, and on other Syrian Facebook pages which had routinely re-shared the port’s data.

But we faced a greater challenge tracking ongoing shipments. We overcame this by searching for news articles as well as social media content posted by dockworkers, which sometimes inadvertently pictured ships docked at the phosphate-loading berths at the port.

Using multiple ship tracking services we were able to monitor these vessels’ movements to- and from- Tartous, which confirmed a pattern we had noticed before: ships docking at the port having turned off their trackers out in the Mediterranean before reappearing sometime later, loaded with phosphates and bound for European ports.

With our partners the Organised Crime and Corruption Reporting Project (OCCRP) and seven of their member centres across Europe, we obtained customs records through freedom of information requests which verified the European customers of Syrian phosphates. The murky supply chain of global middlemen was detailed through scouring corporate records, company sources, national databases and EU and UN trade data.

Finally, we spoke with players in the industry – shippers, buyers and brokers – as well as experts and analysts, to understand how the trade works. Other sources included people on the ground in Syria who confirmed that companies controlled by regime cronies were handling the movement of phosphates from the Russian-controlled mines in the interior to the docks.

STORYLINES

Gennady Timchenko is one of the richest and most powerful men in Russia, a friend and judo partner of Vladimir Putin’s, who became a multi-billionaire working closely with state-owned companies in Russia’s lucrative oil and gas sector. His engineering and construction company, Stroytransgaz, has built multiple export pipelines for Russia’s oil and gas, including the Nord Stream pipeline through Europe.

Timchenko has also been one of the biggest beneficiaries of Moscow’s long-running economic ties with Syria, winning contracts to build part of a gas pipeline from Egypt and two major gas processing plants. After Russian military intervention helped turn the tide of Syria’s civil war in favour of Assad’s regime, two more Stroytransgaz-linked companies secured a dominant position in the phosphates sector — one of the most profitable assets still under government control.

A Stroytransgaz spokesperson insisted it had no ties with these phosphate-trading entities, even though they share the same name, but our investigation mapped multiple overlaps between the companies, including key executives and a shared address in Damascus.

The US has sanctioned Stroytransgaz and Timchenko following the Russian annexation of Crimea in 2014, while the EU has sanctioned Syrian individuals and entities involved in the trade, but neither bans Syrian phosphates specifically.

Ironically, a key destination for the phosphates is Nika Tera port in Ukraine, which is owned by sanctioned pro-Russian oligarch Dmitry Firtash. Ukrainian imports of Syrian phosphates grew from $3 mn-worth in 2018 to $15 mn last year, despite Ukrainian sanctions on both Stroytransgaz and Timchenko.

Karam Shaar, a Syrian economist, said this investigation shows how sanctions can be circumvented by opaque supply chains or by channelling funds and goods through the unknown subsidiaries of targeted companies. “Of course exporting phosphates to Europe is a violation of sanctions,” he said. “But most of the countries don’t understand the structure of the organisations they have sanctioned.”

To keep up to date with Lighthouse investigations sign up for our monthly newsletter

The Impact

Our investigations don’t end when we publish a story with media partners. Reaching big public audiences is an important step but these investigations have an after life which we both track and take part in. Our work can lead to swift results from court cases to resignations, it can also have a slow-burn impact from public campaigns to political debates or community actions. Where appropriate we want to be part of the conversations that investigative journalism contributes to and to make a difference on the topics we cover. Check back here in the coming months for an update on how this work is having an impact.